The

Murder

by John Steinbeck

This

happened a number of years ago in Monterey County, in central California. The

Cañon del Castillo is one of those valleys in the Santa Lucia range[1]

which lie between its many spurs and ridges[2].

From the main Cañon del Castillo a number of little arroyos[3]

cut back into the mountains, oak-wooded canyons, heavily brushed with poison

oak and sage. At the head of the canyon there stands a tremendous stone castle,

buttressed and towered like those strongholds the Crusaders[4]

put up in the path of their conquests. Only a close visit to the castle shows

it to be a strange accident of time and water and erosion working on soft,

stratified sandstone[5].

In the distance the ruined battlements, the gates, the towers, even the arrow

slits, require little imagination to make out.

Below the castle, on the

nearly level floor of the canyon, stand the old ranch house, a weathered and

mossy barn and a warped feeding-shed for cattle. The house is deserted;

the doors, swinging on rusted hinges, squeal and bang on nights when the wind

courses down from the castle. Not many people visit the house. Sometimes a

crowd of boys tramp through the rooms, peering into empty closets and loudly defying

the ghosts they deny.

Jim Moore, who owns the land,

does not like to have people about the house. He rides up from his new house,

farther down the valley, and chases the boys away. He has put “No Trespassing”

signs on his fences to keep curious and morbid people out. Sometimes he

thinks of burning the old house down, but then a strange and powerful relation

with the swinging doors, the blind and desolate windows, forbids the

destruction.

If he should burn the house he would destroy a great and important piece of his life. He knows that when he goes to town with his plump and still pretty wife, people turn and look at his retreating back with awe and some admiration.

****************

Jim Moore was born in the old

house and grew up in it. He knew every grained and weathered board of the barn,

every smooth, worn manger-rack[6].

His mother and father were both dead when he was thirty. He celebrated his

majority[7]

by raising a beard. He sold the pigs and decided never to have any more. At

last he bought a fine Guernsey bull to improve his stock, and he began to go to

Monterey on Saturday nights, to get drunk and to talk with the noisy girls of

the Three Star.

Jim Moore was born in the old

house and grew up in it. He knew every grained and weathered board of the barn,

every smooth, worn manger-rack[6].

His mother and father were both dead when he was thirty. He celebrated his

majority[7]

by raising a beard. He sold the pigs and decided never to have any more. At

last he bought a fine Guernsey bull to improve his stock, and he began to go to

Monterey on Saturday nights, to get drunk and to talk with the noisy girls of

the Three Star.

Within a year Jim Moore

married Jelka Sepic, a Jugo-Slav girl, daughter of a heavy and patient farmer

of Pine Canyon. Jim was not proud of her foreign family, of her many brothers

and sisters and cousins, but he delighted in her beauty. Jelka had eyes as

large and questioning as a doe's eyes. Her nose was thin and sharply

faceted, and her lips were deep and soft. Jelka's skin always startled

Jim, for between night and night he forgot how beautiful it was. She was so

smooth and quiet and gentle, such a good housekeeper, that Jim often thought

with disgust of her father's advice on the wedding day. The old man, bleary and

bloated[8]

with festival beer, elbowed Jim in the ribs and grinned suggestively, so

that his little dark eyes almost disappeared behind puffed and wrinkled lids.

“Don't be big fool, now,” he

said. Jelka is Slav girl. He's[9]

not like American girl. If he is bad, beat him. If he's good too long, beat him

too. I beat his mama. Papa beat my mama. Slav girl! He’s not like a man[10]

that don't beat hell out of him.”

I wouldn't beat Jelka,” Jim

said.

The father giggled and

nudged him again with his elbow. “Don't be big fool,” he

warned. Sometime you see.” He rolled back to the

beer barrel.

Jim found soon enough that

Jelka was not like American girls. She was very quiet. She never spoke first,

but only answered his questions, and then with soft short replies. She learned

her husband as she learned passages of Scripture. After they had been married a while, Jim

never wanted for any habitual thing[11]

in the house but Jelka had it ready for him before he could ask. She was a fine

wife, but there was no companionship in her. She never talked. Her great eyes

followed him, and when he smiled, sometimes she smiled too, a distant and

covered[12]

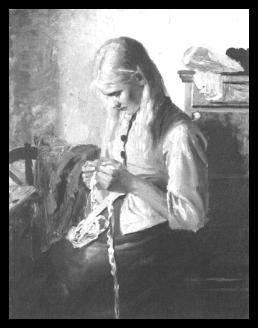

smile. Her knitting and mending and sewing were interminable. There she

sat, watching her wise hands, and she seemed to regard with wonder and pride

the little white hands that could do such nice and useful things. She was so

much like an animal that sometimes Jim patted her head and neck under the same

impulse that made him stroke a horse.

Jim found soon enough that

Jelka was not like American girls. She was very quiet. She never spoke first,

but only answered his questions, and then with soft short replies. She learned

her husband as she learned passages of Scripture. After they had been married a while, Jim

never wanted for any habitual thing[11]

in the house but Jelka had it ready for him before he could ask. She was a fine

wife, but there was no companionship in her. She never talked. Her great eyes

followed him, and when he smiled, sometimes she smiled too, a distant and

covered[12]

smile. Her knitting and mending and sewing were interminable. There she

sat, watching her wise hands, and she seemed to regard with wonder and pride

the little white hands that could do such nice and useful things. She was so

much like an animal that sometimes Jim patted her head and neck under the same

impulse that made him stroke a horse.

In the house Jelka was remarkable. No matter what time Jim came in from the hot dry range[13] or from the bottom farm land, his dinner was exactly, steaming ready for him.

She watched while he ate, and pushed the dishes

close when he needed them, and filled his cup when it was empty.

Early in the marriage he

told her things that happened on the farm, but she smiled at him as a foreigner

does who wishes to be agreeable even though he doesn't understand.

The stallion cut himself on

the barbed wire,” he said.

And she replied Yes,” with a

downward inflection that had neither question nor interest.

He realized before long that

he could not get in touch with her in any way. If she had a life apart[14],

it was so remote as to be beyond his reach. The barrier in her eyes was not one

that could be removed, for it was neither hostile nor intentional.

At night he stroked her straight black hair and her

unbelievably smooth golden shoulders, and she whimpered a little with pleasure.

Only in the climax of his embrace did she seem to have a life apart, fierce and

passionate. And then immediately she lapsed into the alert and painfully

dutiful wife.

Why don't you ever talk to

me?” he demanded. Don't you want to talk to me?”

Yes,” she said. What do you

want me to say?” She spoke the language of his race out of a mind that was

foreign to his race.

When a year had passed, Jim

began to crave the company of women, the chattery exchange of small

talk, the shrill pleasant insults, the shame-sharpened vulgarity[15].

He began to go again to town, to drink and to play with the noisy girls of the

Three Star. They liked him there for his firm, controlled face and for his

readiness to laugh.

Where's your wife?” they

demanded.

Home in the barn,” he

responded. It was a never-failing joke.

Saturday afternoons he

saddled a horse and put a rifle in the scabbard in case he should see a deer.

Always he asked: You don't mind staying alone?”

“No. I don't mind.”

At once he asked: “Suppose

someone should come?”

Her eyes sharpened for a

moment, and then she smiled. “I would send them away,” she said.

“I’ll be back about noon

tomorrow. It’s too far to ride in the night.” He felt that she knew where he

was going, but she never protested nor gave any sign of disapproval. “You

should have a baby,” he said.

Her face lighted up. Some

time God will be good,” she said eagerly.

He was sorry for her

loneliness. If only she visited with the other women of the canyon she would be

less lonely, but she had no gift for visiting. Once every month or so she put

horses to the buckboard[16]

and went to spend an afternoon with her mother, and with the brood of brothers

and sisters and cousins who lived in her father's house.

“A fine time you'll have,”

Jim said to her. “You'll gabble your crazy language like ducks for a whole

afternoon. You'll giggle with that big grown cousin of yours with the embarrassed

face. If I could find any fault with you, I'd call you a damn foreigner.” He

remembered how she blessed the bread with the sign of the cross before she put

it in the oven, how she knelt at the bedside every night, how she had a holy

picture tacked to the wall in the closet.

****************

One Saturday in a hot dusty

June, Jim cut oats in the farm flat[17].

The day was long. It was after six o'clock when the mower tumbled[18]

the last band of oats. He drove the clanking machine up into the barnyard and

backed it into the implement shed, and there he unhitched the horses and turned

them out to graze on the hills over Sunday. When he entered the kitchen Jelka

was just putting his dinner on the table. He washed his hands and face and sat

down to eat.

“I'm tired,” he said, but I think I'II go to Monterey anyway. There'll

be a full moon.”

“I'm tired,” he said, but I think I'II go to Monterey anyway. There'll

be a full moon.”

Her soft eyes smiled.

“I’ll tell you what I’ll do,” he said. “If you would

like to go, I’ll hitch up a rig[19]

and take you with me.”

She smiled again and shook her head. “No, the stores would be closed. I would rather stay here.”

“Well, all right, I’ll

saddle the horse then. I didn't think I was going. The stocks all turned out.

Maybe I can catch a horse easy. Sure you don't want to go?”

“If it was early, and I could

go to the stores—but it will be ten o'clock when you get there.”

“Oh, no—well, anyway, on

horseback I’ll make it a little after nine.”

Her mouth smiled to itself,

but her eyes watched him for the development of a wish. Perhaps because he was

tired from the long day's work, he demanded: “What are you thinking about?”

“Thinking about? I remember,

you used to ask that nearly every day when we were first married.”

“But what are you?” he

insisted irritably.

“Oh—I'm thinking about the

eggs under the black hen.” She got up and went to the big calendar on the wall.

They will hatch tomorrow or maybe Monday.”

It was almost dusk

when he had finished shaving and putting on his blue serge suit and his new

boots. Jelka had the dishes washed and put away. As Jim went through the

kitchen he saw that she had taken the lamp to the table near the window, and

that she sat beside it knitting a brown wool sock.

“Why do you sit there

tonight?” he asked. “You always sit over here. You do funny things sometimes.”

Her eyes arose slowly from

her flying hands. The moon,” she said quietly. You said it would be full

tonight. I want to see the moon rise.”

“But you're silly. You can't

see it from that window. I thought you knew direction better than that.”

She smiled remotely. “I will

look out of the bedroom window, then.”

Jim put on his black hat and

went out. Walking through the dark empty barn, he took a halter[20]

from the rack. On the grassy sidehill he whistled high and shrill. The horses

stopped feeding and moved slowly in towards him, and stopped twenty feet

away. Carefully he approached his bay

gelding[21]

and moved his hand from its rump along its side and up and over its neck. The

halterstrap clicked in its buckle. Jim turned and led the horse back to the

barn. He threw his saddle on and cinched it tight, put his silver-bound bridle

over the stiff ears, buckled the throat latch, knotted the tie-rope about the

gelding's neck and fastened the neat coil-end to the saddle string. Then he

slipped the halter and led the horse to the house. A radiant crown of soft red

light lay over the eastern hills. The full moon would rise before the valley

had completely lost the daylight.

In the kitchen Jelka still

knitted by the window. Jim strode to the corner of the room and took up his

30-30 carbine[22]. As he

rammed cartridges into the magazine[23],

he said: “The moon glow is on the hills. If you are going to see it rise, you

better go outside now. It's going to be a good red one at rising.”

“In a moment,” she replied,

when I come to the end here.” He went to her and patted her sleek head.

“Good night. I'll probably

be back by noon tomorrow.” Her dusky black eyes followed him out of the door.

Jim thrust the rifle into

his saddle-scabbard, and mounted and swung his horse down the canyon. On his right,

from behind the blackening hills, the great red moon slid rapidly up. The

double light of the day's last afterglow and the rising moon thickened the

outlines of the trees and gave a mysterious new perspective to the hills. The

dusty oaks shimmered and glowed, and the shade under them was black as

velvet. A huge, long legged shadow of a horse and half a man rode to the left

and slightly ahead of Jim. From the ranches near and distant came the sound of

dogs tuning up for a night of song. And the roosters crowed, thinking a new

dawn had come too quickly. Jim lifted the gelding to a trot. The spattering

hoof-steps echoed back from the castle behind him. He thought of blonde May at

the Three Star at Monterey. “I’ll be late. Maybe someone else'll have her,” he

thought. The moon was clear of the hills now.

Jim had gone a mile when he

heard the hoofbeats of a horse coming towards him. A horseman cantered up and pulled to a stop. That you, Jim?”

“Yes. Oh, hello, George.”

“I was just riding up to

your place. I want to tell you—you know the springboard[24]

at the upper end of my land?”

“Yes, I know.”

“Well, I was up there this

afternoon. I found a dead campfire and a calf's head and feet. The skin was in

the fire, half burned, but I pulled it out and it had your brand[25].

“The hell,” said Jim. How

old was the fire?”

“The ground was still warm

in the ashes. Last night, I guess. Look, Jim, I can't go up with you. I've got

to go to town, but I thought I'd tell you, so you could take a look around.”

Jim asked quietly, “Any idea

how many men?”

“No. I didn't look close.”

“Well, I guess I better go

up and look. I was going to town too. But if there are thieves working, I don't

want to lose any more stock. I'II cut up through your land if you don't mind,

George.”

“I'd go with you, but I've

got to go to town. You got a gun with you?”

“Oh yes, sure. Here under my

leg. Thanks for telling me.”

“That's all right. Cut

through any place you want. Good night.” The neighbor turned his horse and

cantered back in the direction from which he had come.

For a few moments Jim sat in

the moonlight, looking down at his stilted shadow.

He pulled his rifle from its scabbard, levered a

cartridge into the chamber, and held the gun across the pommel of his saddle.

He turned left from the road, went up the little ridge, through the oak grove,

over the grassy hogback[26]

and down the other side into the next canyon.

In half an hour he had found

the deserted camp. He turned over the heavy, leathery calf's head and felt its

dusty tongue to judge by the dryness how long it had been dead. He lighted a

match and looked at his brand on the half-burned hide. At last he mounted his

horse again, rode over the bald grassy hills and crossed into his own land.

In half an hour he had found

the deserted camp. He turned over the heavy, leathery calf's head and felt its

dusty tongue to judge by the dryness how long it had been dead. He lighted a

match and looked at his brand on the half-burned hide. At last he mounted his

horse again, rode over the bald grassy hills and crossed into his own land.

A warm summer wind was blowing on the hilltops. The

moon, as it quartered up the sky, lost its redness and turned the color of

strong tea. Among the hills the coyotes were singing, and the dogs at the ranch

houses below joined them with broken-hearted howling. The dark green oaks below

and the yellow summer grass showed their colors in the moonlight.

Jim followed the sound of

the cowbells to his herd, and found them eating quietly, and a few deer feeding

with them. He listened for the sound of hoofbeats or the voices of men on the

wind.

It was after eleven when he

turned his horse towards home. He rounded the west tower of the sandstone

castle, rode through the shadow and out into the moonlight again. Below, the roofs of his barn and house shone

dully. The bedroom window cast back a streak of reflection.

The feeding horses lifted

their heads as Jim came down through the pasture. Their eyes glinted redly when

they turned their heads.

Jim had almost reached the

corral fence—he heard a horse stamping in the barn. His hand jerked the gelding

down. He listened. It came again, the stamping from the barn. Jim lifted his

rifle and dismounted silently. He turned his horse loose and crept towards the

barn.

In the blackness he could

hear the grinding of the horse's teeth as it chewed hay. He moved along the

barn until he came to the occupied stall. After a moment of listening he

scratched a match on the butt of his rifle. A saddled and bridled horse was

tied in the stall. The bit[27]

was slipped under the chin and the cinch[28]

loosened. The horse stopped eating and turned its head towards the light.

Jim blew out the match and

walked quickly out of the barn. He sat on the edge of the horse-trough[29]

and looked into the water. His thoughts came so slowly that he put them into

words and said them under his breath.

“Shall I look through the

window? No. My head would throw a shadow in the room.”

He regarded the rifle in his

hand. Where it had been rubbed and, handled, the black gun finish had worn off,

leaving the metal silvery.

At last he stood up with

decision and moved towards the house. At the steps, an extended foot tried each

board tenderly before he put his weight on it. The three ranch dogs came out

from under the house and shook themselves, stretched and sniffed, wagged their

tails and went back to bed.

The kitchen was dark, but

Jim knew where every piece of furniture was. He put out his hand and touched

the corner of the table, a chair back, the towel hanger, as he went along. He

crossed the room so silently that even he could hear only his breath and the whisper

of his trouser legs together, and the beating of his watch in his pocket. The

bedroom door stood open and spilled a patch of moonlight on the kitchen floor.

Jim reached the door at last and peered through.

The moonlight lay on the

white bed. Jim saw Jelka lying on her back, one soft bare arm flung across her

forehead and eyes. He could not see who the man was, for his head was turned

away. Jim watched, holding his breath. Then Jelka twitched in her sleep

and the man rolled his head and sighed—Jelka's cousin, her grown, embarrassed

cousin.

Jim turned and quickly stole back across the kitchen

and down the back steps. He walked up the yard to the water-trough again, and

sat down on the edge of it. The moon was white as chalk, and it swam in the

water, and lighted the straws and barley dropped by the horses' mouths. Jim

could see the mosquito wrigglers, tumbling up and down, end over end, in the

water, and he could see a newt lying in the sun moss in the bottom of the

trough.

He cried a few dry, hard, smothered

sobs[30],

and wondered why, for his thought was of the grassed hilltops and of the lonely

summer wind whisking along.

His thoughts turned to the

way his mother used to hold a bucket to catch the throat blood when his father

killed a pig. She stood as far away as possible and held the bucket at

arms'-length to keep her clothes from getting spattered.

Jim dipped his hand into the trough and stirred the moon to broken, swirling streams of light. He wetted his forehead with his damp hands and stood up. This time he did not move so quietly, but he crossed the kitchen on tiptoe and stood in the bedroom door. Jelka moved her arm and opened her eyes a little. Then the eyes sprang wide, then they glistened with moisture. Jim looked into her eyes; his face was empty of expression. A little drop ran out of Jelka's nose and lodged in the hollow of her upper lip. She stared back at him.

Jim cocked the rifle. The

steel click sounded through the house. The man on the bed stirred uneasily in

his sleep. Jim's hands were quivering. He raised the gun to his shoulder and

held it tightly to keep from shaking. Over the sights he saw the little white

square between the man's brows and hair. The front sight wavered a moment and

then came to rest.

Jim cocked the rifle. The

steel click sounded through the house. The man on the bed stirred uneasily in

his sleep. Jim's hands were quivering. He raised the gun to his shoulder and

held it tightly to keep from shaking. Over the sights he saw the little white

square between the man's brows and hair. The front sight wavered a moment and

then came to rest.

The gun crash tore the air.

Jim, still looking down the barrel, saw the whole bed jolt under the blow. A

small, black, bloodless hole was in the man's forehead. But behind, the

hollow-point took brain and bone and splashed them on the pillow.

Jelka's cousin gurgled in

his throat. His hands came crawling out from under the covers like big white

spiders, and they walked for a moment, then shuddered and fell quiet.

Jim looked slowly back at

Jelka. Her nose was running. Her eyes had moved from him to the end of the

rifle. She whined softly, like a cold puppy.

Jim turned in panic. His

boot heels beat on the kitchen floor, but outside, he moved slowly towards the

water-trough again. There was a taste of salt in his throat, and his heart

heaved painfully. He pulled his hat off and dipped his head into the water.

Then he leaned over and vomited on the ground. In the house he could hear Jelka

moving about. She whimpered like a puppy. Jim straightened up, weak and dizzy.

He walked tiredly through

the corral and into the pasture. His saddled horse came at his whistle.

Automatically he tightened the cinch, mounted and rode away, down the road to

the valley. The squat black shadow traveled under him. The moon sailed high and

white. The uneasy dogs barked monotonously.

****************

At daybreak a buckboard and pair[31] trotted up to the ranch yard, scattering the chickens. A deputy sheriff and a coroner sat in the seat. Jim Moore half reclined against his saddle in the wagon-box. His tired gelding followed behind. The deputy sheriff set the brake and wrapped the lines around it. The men dismounted.

Jim asked, “Do I have to go

in? I'm too tired and wrought up[32]

to see it now.”

The coroner pulled his lip and studied. “Oh, I guess

not. We'll tend to[33]

things and look around.”

Jim sauntered away

towards the water-trough. “Say,” he called, kind of clean up a little, will

you? You know.”

The men went on into the

house.

In a few minutes they

emerged, carrying the stiffened body between them. It was wrapped in a

comforter. They eased it up into the wagon-box. Jim walked back towards them.

“Do I have to go in with you now?”

“Where's your wife, Mr.

Moore?” the deputy sheriff demanded.

“I don't know,” he said

wearily. “She's somewhere around.”

“You're sure you didn't kill

her too?”

“No. I didn't touch her.

I’ll find her and bring her in this afternoon. That is, if you don't want me to

go in with you now.”

“We've got your statement,”

the coroner said. “And by God, we've got eyes, haven't we, Will? Of course

there's a technical charge of murder against you, but it'll be dismissed. Always is in this part of the country. Go

kind of light on your wife, Mr. Moore.”

“I won't hurt her,” said Jim.

He stood and watched the

buckboard jolt away. He kicked his feet reluctantly in the dust. The hot

June sun showed its face over the hills and flashed viciously on the bedroom

window.

Jim went slowly into the

house, and brought out a nine-foot, loaded bull whip. He crossed the yard and

walked into the barn. And as he climbed the ladder to the hay-loft, he heard

the high, puppy whimpering start.

When Jim came out of the

barn again, he carried Jelka over his shoulder. By the water-trough he set her

tenderly on the ground. Her hair was littered with bits of hay. The back of her

shirtwaist was streaked with blood.

Jim wetted his bandana at

the pipe and washed her bitten lips, and washed her face and brushed back her

hair. Her dusty black eyes followed every move he made.

“You hurt me,” she said.

“You hurt me bad.”

He nodded gravely. “Bad as I

could without killing you.”

The sun shone hotly on the

ground. A few blowflies buzzed about, looking for the blood.

Jelka's thickened lips tried

to smile. “Did you have any breakfast at all?”

“No,” he said. “None at

all.”

“Well, then, I’ll fry you up

some eggs.” She struggled painfully to her feet.

“Let me help you,” he said.

“I’ll help you get your shirtwaist off. It's drying stuck to your back. It'll

hurt.”

“No. I’ll do it myself.” Her

voice had a peculiar resonance in it. Her dark eyes dwelt warmly

on him for a moment, and then she turned and limped into the house.

Jim waited, sitting on the

edge of the water-trough. He saw the smoke start out of the chimney and sail

straight up into the air. In a few moments Jelka called him from the kitchen

door.

“Come, Jim. Your breakfast.”

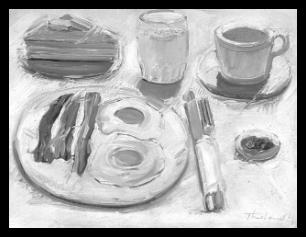

Four fried eggs and four

thick slices of bacon lay on a warmed plate for him. “The coffee will be ready

in a minute,” she said.

“Won't you eat?”

“No. Not now. My mouth's too

sore.”

He ate his eggs hungrily and

then looked up at her. Her black hair was combed smooth. She had on a fresh

white shirtwaist. “We're going to town this afternoon,” he said. I’m going to

order lumber. We'll build a new house farther down the canyon.”

Her eyes darted to the

closed bedroom door and then back to him. “Yes,” she said.

“That will be good.” And then, after a moment, “Will

you whip me any more—for this?”

“No, not any more, for

this.”

Her eyes smiled. She sat

down on a chair beside him, and Jim put out his hand and stroked her hair and

the back of her neck.

****************